Pathology of eyelid tumors

pyright and License information ►Anatomy and Histology of the Eyelid

In spite of being a small organ, the eyelids contain numerous histological elements that can be the origin of benign and malignant lesions.

The eyelids are composed of four layers: Skin and subcutaneous tissue, striated muscle (orbicularis oculi), tarsus, and conjunctiva.[

1]

The eyelid skin is the thinnest in the body and lacks subcutaneous fat, but otherwise contains all other skin structures. The skin epithelium is keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Melanocytes are spread in the basal layer of the epithelium. The dermis contains fibrous tissue, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves.

The eyelids are rich in glandular tissue: The eccrine glands – the sweat glands of the eyelid skin and the accessory lacrimal gland of Krause and Wolfring; the apocrine gland of Moll; and the sebaceous glands – the meibomian glands and the glands of Zeiss.

The entire orbital entrance is covered by the orbicularis oculi – a striated muscle that is composed of pretarsal and preseptal parts and the orbital part that is located over the external orbital bones. The tarsi are firm plates composed of dense connective tissue, and the meibomian glands are embedded in the connective tissue of the tarsal plates.

The posterior eyelid surface is lined by the palpebral conjunctiva that is composed of epithelium and subepithelial stroma – the substantia propria. The epithelium of the tarsal conjunctiva is mostly cuboidal and contains goblet cells. Melanocytes are scattered in the basal layer of the epithelium. The stroma is composed of fibrovascular connective tissue.

Classification of Eyelid Tumors

As tumors in other organs, tumors of the eyelid can be classified according to their tissue or cell of origin and as benign or malignant.[

2,

3] lists the eyelid tumors according to their origin. Most of the eyelid tumors are of cutaneous origin, mostly epidermal, which can be divided into epithelial and melanocytic tumors. Benign epithelial lesions, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), cystic lesions, and melanocytic lesions represent about 85% of all eyelid tumors.[

4] Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and melanoma are relatively rare. Adnexal and stromal tumors are less frequent. Other tumors of the eyelid are lymphoid tumors, hamartomas, and choristomas. Inflammatory and infectious lesions that can simulate neoplasms are common. Only the more common benign and malignant eyelid tumors are included in this review. Tumors of the palpebral conjunctiva are included in the review on conjunctival pathology.

Major types of eyelid tumors

Epithelial Eyelid Tumors

Tumors of the skin epithelium can be divided according to their clinical behavior and histologic findings into three main groups: Benign, precancerous, and malignant tumors.

Benign epithelial tumors

The most common benign tumors of the eyelid skin epithelium are squamous papilloma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, seborrheic keratosis, keratoacanthoma, and inverted follicular keratosis.

Squamous papilloma

Squamous papilloma is the most common benign epithelial tumor of eyelid and is often sessile or pedunculated with papillary shape and keratinized surface. Squamous papillomata may be multiple. It typically occurs in middle-aged or older adults [].

Squamous papilloma presenting as a papillary lesion in the upper lid margin

Histopathologically, the papilloma consists of papillomatous structures of benign squamous epithelium showing variable levels of acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, and sometimes focal parakeratosis, overlying a fibrovascular core, and may show some chronic inflammation [].

Histopathology picture of papillomatous lesion showing epithelial acanthosis and some hyperkeratosis with a central fibrovascular core (H and E, ×4)

Seborrheic keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis is a common benign skin lesion that affects middle-aged and older individuals. They are well-demarcated warty plaques that may vary in size, degree of pigmentation, and shape of surface which may be greasy.[

5]

Histologically, seborrheic keratosis is a lesion above the skin surface, showing acanthotic proliferation of basaloid cells with various degrees of hyperkeratosis and keratin-filled cystic inclusions. When hyperkeratosis is more prominent, the lesion is more papillomatous whereas when the keratinization is minimal and the epithelium shows more elongated and broaching epithelial strands, it is considered to be the adenoid type of seborrheic keratosis. The pigmentation is due to the transfer of melanin into the keratinocytes. When the seborrheic keratosis is irritated, the dermis exhibits chronic inflammation.

Inverted follicular keratosis

This is a benign, solitary nodular or papillary keratotic mass that may be pigmented and most frequently occurs at the eyelid margin. In general, the lesion is of recent onset and has a tendency to recur if incompletely excised and can easily be mistaken for SCC.[

6]

Histopathologically, it shows endophytic proliferation of both basaloid and squamous elements with frequent presence of squamoid eddies and variable pigmentation, acantholysis, and chronic inflammation. There are those who consider it as a form of irritated seborrheic keratosis.

Pseudoepitheliomatous (pseudocarcinomatous) hyperplasia

This is a reactive process that may clinically and histopathologically be confused with basal cell or SCC. These lesions are usually elevated with an irregular surface, sometimes with ulceration or crust, and may occur anywhere in the eyelid and typically are of short duration. It is usually associated with chronic inflammation and occurs as a reaction to trauma, surgical wound, burns, radiotherapy, cryotherapy, mycotic infections, insect bites, or topical drugs. It may be evoked by certain tumors such as lymphoma.

Histopathologically, these lesions show invasive elongated processes of hyperplastic epithelium which may anastomose. The lesions are frequently infiltrated by inflammatory cells, with occasional multinucleated giant cells and eosinophils. The epithelium shows normal maturation, and disturbing cytologic features such as dysplasia and atypical mitoses are usually absent; however, cytologic atypia may occur, and differentiation from SCC may be difficult.[

7]

Keratoacanthoma

This lesion is typically a dome-shaped nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and elevated, rolled margins. It usually develops over a short period of weeks to a few months and may regress spontaneously. There is a long-standing debate as to whether those lesions are benign reactive lesions or a variant of SCC.[

8]

Histopathologically, these lesions disclose typically a cup-shaped nodular elevation with thickened epidermis containing islands of well-differentiated squamous epithelium that may be infiltrated by neutrophils surrounding a central mass of keratin. The lesion base is often well-demarcated from the adjacent dermis by inflammatory reaction.

Cutaneous horn (nonspecific keratosis)

These are hyperkeratotic lesions that may be associated with a variety of benign or malignant lesions. There are no specific histopathologic findings other than hyperkeratosis.

Premalignant and malignant epithelial eyelid tumors

Actinic keratosis (solar keratosis)

This is the most common precancerous cutaneous lesion. It usually occurs in sun-exposed areas of the skin, including eyelids, in fair-skinned middle-aged patients, and is a result of damage of the epidermal cells by near ultraviolet radiation. Clinically, actinic keratosis appears as a single or multiple small erythematous, scaly, sessile lesions and sometimes may show a nodular, horny, or warty configuration. Patients with actinic keratosis may have other cutaneous malignancies. Actinic keratosis may transform to SCC, but it is not clear what percentage will undergo this transformation. Today, actinic keratosis is considered an incipient form of SCC and those carcinomas arising from actinic keratosis are low grade.[

9]

Histopathologically, the epithelium of the lesion shows varying degrees of squamous dysplasia with loss of cell polarity and dysmaturation, significant hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis although, generally, the mitotic activity is low. Acantholysis is sometimes seen in the basal cells. It typically involves the interfollicular epidermis, sparing the adnexal structures. The dermis under the lesion shows varying degrees of solar elastosis and chronic inflammation. According to the predominant histologic features, four subtypes of actinic keratosis have been recognized: Hypertrophic, atrophic, acantholytic, and lichenoid. Actinic keratosis is often seen in the margins of invasive SCC.

Xeroderma pigmentosum

This is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder of DNA repair in which the ability of repair damage caused by ultraviolet light is deficient. It affects sun-exposed areas of the skin and mucous membranes. In the advanced stage of xeroderma pigmentosum, various types of malignant neoplasm develop including SCC, BCC, malignant melanoma, and different types of sarcomas.[

10]

Basal cell carcinoma

BCC is the most common skin malignancy and, in non-Asian countries, accounts for 85–95% of all malignant epithelial tumors of the eyelid.[

5] The lower eyelid and inner canthus are most commonly affected. BCC affects mostly adults, and it rarely occurs in children who do not have a predisposing disease. Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light is the most important risk factor. In most cases, BCC appears as a solitary lesion.

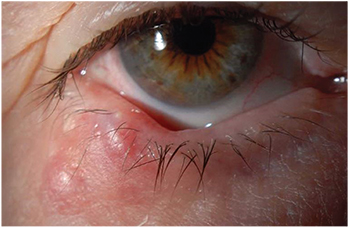

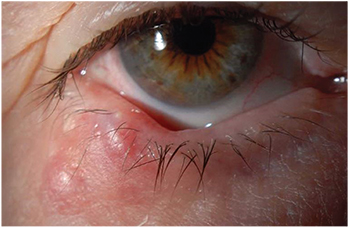

Several clinical types of BCC have been described: Nodular and noduloulcerative, pigmented, and infiltrating (morphea or sclerosing) are common types of BCC in the eyelid. Other types such as superficial BCC are less common in eyelid and are seen mostly in other locations. BCC in the eyelid is usually painless and accompanied by loss of eyelashes. The more common nodular type appears clinically as a raised, firm, pearly nodule, often exhibiting small telangiectatic vessels on its surface. As the nodule increases in size, it may undergo central ulceration []. Pigmented BCC is similar to the nodular or noduloulcerative type, with the presence of amelanotic pigmentation. The infiltrating type appears as a pale, indurated plaque with ill-defined borders. Metastatic BCC is extremely rare; however, local invasion to adjacent tissue, mainly the orbit, may occur, especially when BCC is located in the inner canthus and is of the infiltrating type. Intraocular invasion is rare.

Basal cell carcinoma of the lower eyelid presenting as an elevated ulcerated nodule

Histopathologically, the two main types of BCC are the solid, circumscribed type, which mostly correlates with the clinical nodular type, and the morphea/sclerosing type, which correlates with the clinical infiltrating type.[

11] The solid type is composed of epithelial lobules of cells with oval nuclei and scanty cytoplasm with prominent peripheral palisading of the nuclei []. Differentiated solid BCC with adnexal features is referred to as keratotic, cystic, or adenoid types. The morphea pattern is characterized by elongated strands of basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma. This type of BCC is aggressive and deeply infiltrating into the adjacent dermis, and in more advanced stages into the orbital structures and paranasal sinuses, and rarely, intraocularly. The superficial type may show diffuse multicentric involvement of the epidermis extending into the superficial dermis.[

5] Histological differential diagnosis of BCC is sometimes challenging, especially with adnexal tumors such as sebaceous carcinoma and trichoepithelioma. A special variant of BCC is the basosquamous carcinoma which shows morphologic features that are intermediate between those of BCC and those of squamous cell carcinoma.

Histopathology pictures of a solid-type of basal cell carcinoma composed of nodules of epithelial tumor cells lined by peripheral palisading of the nuclei (H and E, ×10)

Squamous cell carcinoma

Eyelid SCC is an invasive tumor arising from the squamous cell layer of the skin epithelium and affects mainly elderly fair-skinned individuals. The most common risk factor is exposure to ultraviolet light. Most commonly, it involves the lower lid margin and inner canthus. In the upper eyelid and outer canthus, it is more common than BCC. SCC in the eyelids is much less common than BCC, comprising about 5% of all eyelid malignancies.[

5] It may arise de novo but often it may arise from preexisting lesions such as actinic keratosis, xeroderma pigmentosum, carcinoma in situ (Bowen's disease), or following radiotherapy.

Clinically, SCC is most commonly an elevated painless indurated plaque or nodule, often with central ulceration and irregular rolled borders. It may have other presentations such as papillomatous lesion or cutaneous horn. Most eyelid SCCs have an excellent prognosis; however, advanced and neglected cases tend to recur locally and may spread locally to adjacent structures such as the orbit and lacrimal drainage system, and even to the intracranial cavity. Unlike BCC, eyelid SCC may metastasize to the preauricular and submandibular lymph nodes and even to distant organs. The high TNM and the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging are associated with local recurrence and metastasis.[

12,

13]

The histopathologic feature of SCC depends on the degree of differentiation of the tumor. In well-differentiated tumors, the cells are polygonal with abundant acidophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with various size and staining properties, dyskeratotic cells, and easy-to-find intercellular bridges. Poorly differentiated SCC shows pleomorphism with anaplastic cells, abnormal mitotic figures, little or no evidence of keratinization, and loss of intercellular bridges. Variants of SCC are spindle and adenoid SCC. Keratoacanthoma has recently been considered as a variant of SCC.

Melanocytic Eyelid Tumors

Benign melanocytic eyelid tumors

Melanocytic lesions of the skin are common and may arise from nevus cells, melanocytes of the epidermis, and melanocytes of the dermis; all derive embryologically from the neural crest. The location of the melanocytic cells affects the clinical appearance of the various types of the melanocytic lesions.

Freckles (ephelis)

Freckles are small, flat brown skin spots scattered over sun-exposed areas, including the eyelids that characteristically darken with sunlight exposure and fade in the absence of sunlight. Histologically, there is hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer but no elongation of the rete ridges.[

5]

Lentigo simplex

These lesions are small, flat brown-to-black lesions that clinically are indistinguishable from junctional nevi. They are not affected by exposure to light. Histologically they show an increase in number of basal melanocytes with elongation of the rete ridges and scattered melanophages in the upper dermis.[

5]

Solar lentigo

These lesions are light to dark brown in color and develop in chronically sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the back of the hand, in over 90% of elderly Caucasians. They may appear on the eyelids. As lentigo simplex, they show histologically an increase in the number of melanocytes in the basal cell layers and elongation of the rete ridges which are club-shaped and exhibit irregular tortuosity.[

5]

Eyelid nevi

Eyelid nevi are common benign melanocytic lesions that show clinical and histological varieties.

Congenital nevus

Congenital nevi are common, present in the skin in about 1% of newborns. They may vary in size from small to giant[

14] and have a small lifetime risk for malignant transformation. Histopathologically, nevus cells usually involve the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue with perifollicular and perivascular distribution.

Unique eyelid congenital nevi are the “split nevus,” known as the “kissing nevus,” and nevus of Ota. The split nevus involves both upper and lower eyelids, suggesting their development between the 9

th and 20

thweek of gestation when the eyelids are fused [].[

15] Histologically, these nevi are compound nevi.

Clinical picture of a “split nevus,” also known as “kissing nevus”

Nevus of Ota (oculodermal melanocytosis) presents as a unilateral bluish discoloration of the eyelid and periorbital skin, in addition to blue scleral discoloration []. Bilateral involvement is rare. Histologically, the skin shows proliferation of dendritic and plump polyhedral melanocytes in the dermis. The uvea also shows proliferation of melanocytes. Patients with nevus of Ota have a small risk of developing cutaneous or uveal melanoma.[

16,

17]

Oculodermal melanocytosis, known as nevus of Ota, showing unilateral bluish discoloration of the eyelid and periorbital skin and blue scleral discoloration

Another variant of congenital nevus that may affect the eyelid is the blue nevus and its subtype, the cellular blue nevus. These nevi are blue because of the deep location of the dendritic melanocytes in the dermis, which causes the Tyndall phenomenon. Blue nevi can rarely undergo malignant transformation.[

18] It is interesting to note that, unlike conventional melanocytic nevi, blue nevi do not show BRAF and NRAS mutations, but rather GNAQ mutations that are often seen in uveal melanoma.[

19]

Acquired nevi

Acquired nevi develop in childhood and may grow during adolescence. Sun exposure may affect their development and density. They can be located anywhere in the eyelid skin and eyelid margin and may involve the conjunctiva. The nevi are flat or elevated, usually pigmented, lesions.

Histologically, the three main types of acquired nevus, according to the location of the nevus cells, are the junctional nevus, located in the dermoepidermal junction, the intradermal nevus, located only in the dermis, and the compound nevus, which involves both dermoepidermal junction and dermis.[

5] Junctional nevi are relatively rare and are seen in younger patients; with advancement of age, more compound nevi and later intradermal nevi are seen. While junctional and compound nevi can undergo malignant changes, the intradermal nevus, the most common and most benign type of nevus, very rarely transforms to melanoma.

Nevus cells can be small or large, usually with round to oval or elongated spindle-shaped nuclei with various amounts of melanin. They often are organized in nests of nevus cells. Occasionally balloon cells, which are larger than the conventional nevus cells, with smaller nuclei and more cytoplasm, can be seen.

Several types of nevus have a higher potential for malignant transformation.[

20] Spitz nevus, a rapidly growing red- or tan-colored lesion, usually appears in childhood and adolescence. Histopathologically, these are compound nevi that may show mitotic figures. Atypical/dysplastic nevus, a common nevus in the Caucasian population, is irregular and a larger nevus with variegated colors. In familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome, an autosomal dominant syndrome due to mutations of the gene CDKN2A on chromosome 9, nevi tend often to transform to melanoma. These high-risk nevi are rare on the eyelids.

Cutaneous melanoma of eyelid

Melanoma of the eyelid skin is very rare, representing <1% of all malignant neoplasms of the eyelid skin.[

21,

22] Ultraviolet radiation most likely contributes to its development, which occurs mostly in fair-skinned elderly adults. Oculodermal melanocytosis is also considered a risk factor for the development of melanomas. Eyelid cutaneous melanoma arises most frequently in the lower eyelid and can appear de novo or grow from a preexisting pigmented lesion that increases in size and changes in shape and color.

It is likely that most eyelid melanomas evolve through the flat lentigo maligna precursor lesion that progresses to lentigo maligna melanoma or through dysplastic nevi. Nodular melanomas are rare among the already very rare cutaneous eyelid melanomas. Eyelid melanoma can often involve the eyelid margins. In such cases, the mucocutaneous junction may be breeched and the palpebral conjunctiva may be involved. It may be difficult to know whether the melanoma originates in the skin or in the conjunctiva. Such cases have a worse prognosis.[

21]

Histopathologically, lentigo maligna shows atypical melanocytes in the basal layers of the epidermis and may be identified along adnexal structures as the pilar units of the eyelashes. Any breach of the epidermal basement membrane by atypical melanocytes is considered malignant melanoma. Melanoma can develop also from an intradermal melanocytic lesion. Clark's microstaging of cutaneous melanoma does not apply to the eyelid skin that has a different structure of its dermis. Prognostic parameters, in addition to eyelid margin involvement, are depth of invasion of the melanoma and presence of ulceration, which is seldom seen in cutaneous eyelid melanoma. Regional lymph node and distant metastases causing mortality were reported, but the mortality rate varies significantly due to the rarity of cutaneous eyelid melanoma.[

21]

Adnexal Tumors of the Eyelid

The eyelid adnexal tumors may be classified as cystic lesions and benign and malignant solid lesions. They originate from hair follicles, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and accessory lacrimal glands. Cystic lesions may occur due to duct obstruction, trauma, surgery, or inflammatory process. The precise etiology of the solid adnexal tumors is mostly unknown.[

23]

Cystic lesions

Epidermal inclusion cysts (epidermoid cysts)

These cysts usually present a smooth dome-shaped elevation of varying size that may have an opening. They may be pigmented. Histopathologically, a cystic space is filled with keratin and lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. When a cyst is ruptured, reactive inflammation can develop around it.

Hidrocystoma

Hidrocystomas are common cysts, arise from sweat glands, and are also known as sudoriferous cysts or ductal cysts of sweat gland origin. They are divided into two types such as apocrine and eccrine.[

5]

Apocrine hidrocystoma

This is a retention cyst which usually appears as a solitary translucent, often bluish, cystic nodule in the eye margin of adult people [].[

23,

24] It originates from a blocked excretory duct of a Moll's gland. The cyst is filled with clear or milky fluid. It usually measures 1–3 mm in diameter but may reach 10–15 mm in diameter. Occasionally, multiple lesions are encountered.

Apocrine hidrocystoma presenting as a bluish cyst

Histopathologically, the lesion can have one or several cystic spaces typically lined by two layers of cells: The inner columnar epithelium that displays typical eosinophilic apical cytoplasm and the decapitation secretion, surrounded by outer myoepithelial cells [].

Histopathological picture of apocrine hidrocystoma showing cystic spaces lined by inner columnar epithelium that displays typical eosinophilic apical cytoplasm – the decapitation secretion, surrounded by outer myoepithelial cells (H and E, ×40) ...

Eccrine hidrocystoma

This ductal retention cyst of eccrine sweat glands appears as a solitary clear cystic lesion on an eyelid of an adult person, but not in the eyelid margin.[

23,

24] It measures 4–10 mm in diameter [].

Eccrine hidrocystoma in the lateral canthus

Histopathologically, the lesion contains one cystic space lined by two layers of small cuboidal epithelial cells, occasionally one layer lines the cyst. No myoepithelial cells are present [].

Histopathological picture of eccrine hidrocystoma showing cystic spaces lined by two layers of cuboidal epithelium (H and E, ×10)

Trichilemmal (pilar) cysts

These are cysts of the pilosebaceous follicles that are common in the scalp but relatively rare in the eyelids. Clinically, they are similar to epidermal inclusion cysts, showing smooth elevation.

Histopathologically, the cyst shows epithelial lining, which in the periphery is basophilic with distinct palisading nuclei, and toward the lumen are squamous epithelial cells that slough off into the lumen as keratin without formation of a granular layer.[

25] Calcifications may occur. If the cyst is ruptured, foreign body granulomatous reaction can be seen around the cyst wall.

Milia represent small umbilicated retention cysts of the pilosebaceous units. Histologically, the lesion displays a dilated hair follicle and may show a pore opening through the epidermis.

Sweat gland tumors

There are two types of sweat glands such as eccrine and apocrine. In the eyelids, eccrine sweat glands are distributed over the eyelid skin while the apocrine glands are the glands of Moll that are associated with eyelashes and, therefore, their tumors are usually in the eyelid margin.

Syringomas

Syringoma is a common benign eccrine sweat gland tumor of the eyelid, especially in young women. The lesions are usually multiple and appear as yellowish, waxy nodules measuring 1–3 mm.

Histopathologically, the nodules are composed of small ductal elements embedded in a dense fibrous tissue. The walls of the ducts are usually lined by two rows of epithelial cells without myoepithelial cells.[

5]

Pleomorphic adenoma

Pleomorphic adenoma of the skin, known also as benign mixed tumor or chondroid syringoma, is very rare in the eyelids. They arise from skin sweat glands and clinically appear as intradermal multilobulated mass. Histologically, they are identical to pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal glands.[

5]

Eccrine spiradenoma

This rare benign lesion in the eyelids, known also as hidradenoma or acrospiroma, appears clinically as a single subcutaneous nodule. The skin over the dermal nodule appears reddish. Histologically, the lesion is well-circumscribed and shows two types of cells: The peripheral basophilic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and the pale glycogen-rich clear cells. Malignant variants of these tumors have been reported.[

5]

Sweat gland adenocarcinomas

These are rare malignant tumors in the eyelids and may arise from eccrine and apocrine glands (glands of Moll). They may present as a slowly growing lesion of various shapes and colors.

The eccrine sweat gland adenocarcinoma (malignant syringoma) shows histologically solid cords of cells with or without ductal lumina and squamous microcysts, embedded in dense fibrous tissue.[

26]

Mucinous sweat gland adenocarcinoma has a predilection for the eyelid and may present as a solid or cystic eyelid margin lesion. These rare tumors of eccrine origin show histologically elongated cords and lobules of epithelial tumor cells embedded in pools of mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septae. Tumor islands may show glandular differentiation with gland-like lumina.[

27]

Apocrine gland of Moll adenocarcinoma is an extremely rare tumor of the eyelid margin. Histologically, it may show glandular arrangement of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with typical decapitation secretion.[

28]

A few cases of primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the eyelid were reported. In such cases, lacrimal gland origin, such as the glands of Wolfring, should be ruled out.[

5]

Hair follicle tumors

Trichoepithelioma

These are benign tumors of hair follicle origin and may appear solitary, usually acquired in adults, or multiple, usually inherited in children and adolescents. They appear as a firm elevated nonulcerated skin-colored nodule.

Histologically, the tumor shows multiple horny cysts with fully keratinized centers surrounded by islands of proliferating basaloid cells that are sometimes difficult to distinguish from BCC. The stroma of the tumor is well-demarcated from the surrounding dermis. When high differentiation exists, abortive formations of hair papillae and hair shafts can be seen.[

5]

Trichofolliculoma

This is a hamartoma representing the most differentiating form of hair follicle tumors. Clinically, it appears as a single, slightly elevated, dome-shaped nodule, often with a central umbilication with white hairs growing from it.

Histologically, the lesion is composed of a dilated cystic structure which is a dilated hair follicle, lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium that is continuous with the surface epithelium. The lumen usually contains several hair shafts. The central cystic structure shows branching of abortic pilar structures and may be surrounded by such structures in the connective tissue around it. Reactive granulomatous inflammation can be seen around the hair shaft fragments.[

29]

Trichilemmoma

This is a benign tumor that arises from the outer layers of the hair follicle in adults. Clinically, they appear as a small nodule with either smooth skin-colored papules or warty lesion with irregular rough surface that can be mistaken for verruca or cutaneous horn.

Histologically, the lesions show lobular acanthosis of glycogen-rich clear cells with often palisading cells with distinct basal membrane in its periphery. Hair follicles may be seen in the lesion.[

30]

Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma of malherbe)

This is usually a slow-growing, solitary solid or cystic, pink-to-purple subcutaneous lesion, originating from hair matrix cells, and often seen in young patients in the upper lid or eyebrow. Pilomatrixoma is often misdiagnosed clinically.

Histologically, the tumor appears as a well-demarcated tumor that typically consists of two cell populations: The basophilic basaloid cells at the periphery of the lesion, and pale ghost cells toward the center. With aging, more basaloid cells transform to ghost cells. Most of the tumors show varying degrees of calcifications that may elicit foreign body granulomatous inflammation. Ossification can also be found in the lesion. Mitotic figures which are not abnormal can indicate rapid proliferation. Malignant transformation is rare.[

31]

Carcinoma of hair follicles

Malignant tumors of hair follicles in the eyelid, including malignant transformation of benign lesions, are very rare and histologically show a resemblance to BCC.

Sebaceous gland tumors

Tumors of the sebaceous glands in the ocular region originate in the meibomian glands, glands of Zeis, the caruncle, and the skin of the eyebrow.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia

These lesions present as a yellowish, elevated, soft, often umbilicated nodule in elderly people.

Histologically, they are composed of well-demarcated lobules of fully mature but hyperplastic sebaceous glands usually surrounding centrally located dilated sebaceous duct.[

5]

Sebaceous gland adenoma

These are rare lesions presenting clinically as tan, yellow, or reddish nodules in elderly people. If it appears in a young person, it may indicate Muir–Torre syndrome.[

32] Histologically, sebaceous gland adenoma displays similar features to those observed in sebaceous gland hyperplasia.

Sebaceous gland carcinoma

Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) is a highly malignant tumor, the second most common malignant eyelid tumor in Caucasians, and accounts for about 5% of these tumors. However, in Asian countries such as India, China, and Japan, it is as prevalent as or even more common than eyelid BCC.[

33] This is a very malignant tumor, capable of aggressive local invasion as well as metastasis to regional lymph nodes and distant organs, causing mortality in about 30%,[

34] although improved management in recent years has decreased the mortality to <10%.[

35] SGC is generally a disease of elderly patients, is more common in women, and is more common in the upper eyelid. SGC in younger individuals may appear after radiation to the periocular region.

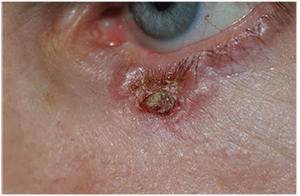

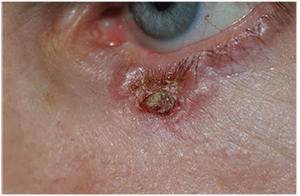

Clinically, SGC of the eyelid may present as a solitary nodule or as a diffuse process. The more common solitary nodule presents as a firm, painless subcutaneous lesion, arising and fixed to the tarsus, or appears in the eyelid margin when it arises from the gland of Zeis. SGC may mimic chalazion; however, unlike chalazion, SGC causes loss of eyelashes []. SGC may present diffuse thickening of the eyelid and may involve the forniceal and bulbar conjunctiva. In such cases, the patient may initially be diagnosed with persistent unilateral blepharitis or conjunctivitis because of the tendency of the SGC to invade the overlying epithelium. SGC of the caruncle appears as an irregular yellow mass.[

33]

Sebaceous gland carcinoma of the upper eyelid presenting as red thickening of the upper eyelid with loss of eyelashes

Histopathologically, SGC can be classified by the degree of differentiation of their cells. Well-differentiated tumors contain neoplasic cells that exhibit sebaceous differentiation, showing vacuolated foamy-frothy cytoplasm. In moderately differentiated tumors, a majority of the neoplastic cells show hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and basophilic cytoplasm, and a few areas show high sebaceous differentiation. Poorly differentiated tumors display the features of an anaplastic tumor with hyperchromatic and often atypical cells, with marked pleomorphism and high mitotic activity. In comedocarcinoma pattern of SGC, the center of the tumor shows necrosis. Oil Red O staining for lipids is very helpful in establishing the diagnosis [].[

5] Several immunostainings such as human milk fat globulin-1 can replace the routine Oil Red O staining, helping to differentiate SGC from BCC and SCC.[

34]

Histopathological picture of sebaceous gland carcinoma of the meibomian gland stained with Oil Red O (×10)

SGC often shows intraepithelial spread into the eyelid epidermis and the conjunctival epithelium, which is usually referred to as “pagetoid spread.”[

33] It may also spread directly into adjacent structures such as the orbit, paranasal sinus, and intracranial cavity. The poorly differentiated SGC may show perineural infiltration and invasion into the lymphatics. It may metastasize to the regional lymph nodes as well as to distant organs, causing mortality in about 30%,[

35] although improved management in recent years has reduced the mortality to <10%.[

36]

Stroma Tumors of Eyelid

Most of the eyelid stromal tumors are rare. They can be classified according to their tissue of origin: Fibrous tissue tumors, fibrohistiocytic tumors, lipomatous tumors, smooth muscle tumors, skeletal muscle tumors, neural tumors, lymphoid and leukemic tumors, bone and cartilage tumors, secondary tumors, metastatic tumors, and hamartomas and choristomas. Because of their rarity, most of these tumors are mentioned here briefly, and only the more common tumors are reviewed.

Fibrous tissue tumors

Fibromas

These are rare congenital, developmental, or acquired lesions with a tendency to involve the lower eyelid. Histologically, the typical fibroma is sparsely cellular with prominent collagen bundles separated by compressed fibroblasts.[

37]

Nodular fasciitis

Nodular fasciitis of the eyelid is rare; it presents as a solitary subcutaneous nodule, which often resolves spontaneously. Histologically, it is an infiltrative lesion consisting of proliferation of immature fibroblasts with thin spaces between them. The lesions may show endothelial proliferation, lipid-laden macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and acute and chronic inflammatory cells. Because of its pleomorphic cells and frequent mitotic figures, it may be mistaken for a malignant neoplasm.[

37]

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma of the eyelid is a rare, highly malignant tumor and can be locally destructive and can metastasize. It presents as a rapidly progressive solitary eyelid nodule or as a second malignancy in patients with genetic retinoblastoma, mainly after radiotherapy. Histologically, the tumor consists of closely packed cells showing an interlacing woven herringbone pattern, with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli.[

37]

Fibrohistiocytic tumors

These lesions can be classified as benign and malignant and as localized lesions and eyelid lesions in systemic diseases.

Xanthelasma

Xanthelasma palpebrarum is a very common localized, usually bilateral subcutaneous eyelid lesion. Most patients with xanthelasma are normolipemic, but about one-third have primary hyperlipidemia, especially Types II and III, and also patients with secondary hyperlipidemia.

Clinically, xanthelasma occurs in middle-aged or elderly patients as flat or slightly elevated yellowish-tan soft plaques in the inner canthi. Histologically, the lesions are composed of collections of lipid-laden histiocytes in the superficial dermis, mainly around blood vessels and adnexa.[

5,

37]

Juvenile xanthogranuloma

Eyelid lesions in juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) may appear as a localized solitary lesion or as a part of a systemic disease. JXG is a nonneoplastic, often self-limited, histiocytic proliferation, which usually starts in infancy. The most common ocular site of JXG is the iris. The eyelid lesion appears as an elevated orange or reddish-brown nodule. Adult-onset eyelid xanthogranuloma has been reported.

Histopathologically, the lesions of JXG are typically composed of monomorphic infiltrate of histiocytes, intermixed with lymphocytes and the classic multinucleated Touton giant cells.[

5,

37]

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma

These lesions may appear in the eyelids of adults in association with systemic monoclonal gammopathies, usually IgG, and with plasma cell dyscrasias. Clinically, the subcutaneous eyelid lesion may have an indurated character and a waxy yellowish or erythematous appearance. The eyelid lesion may extend into the orbit.

Histopathologically, these granulomas are characterized by collagen necrobiosis surrounded by inflammatory cells, including foamy histiocytes and multinucleated Touton giant cells.[

38]

Fibrous histiocytoma

The eyelids are a rare location for fibrous histiocytoma (FH) that may involve superficially the eyelid skin and deeply the tarsus. Clinically, it appears as a solid mass covered by intact skin. FH may be benign or malignant. The malignant FH can invade locally the surrounding tissue and may metastasize.

Histopathologically, the tumor consists of interlacing fascicles of fibroblastic cells that exhibit a storiform pattern, intermixed with large histiocytes. Multinucleated Touton giant cells are common. Malignant FH exhibits marked nuclear pleomorphism and high mitotic activity.[

5,

37]

Vascular tumors

Benign vascular tumors of the eyelid can be congenital hamartomatous lesions such as capillary hemangioma, nevus flammeus and anteriovenous malformation, or acquired such as cavernous hemangioma and granulation tissue. Malignant vascular tumors of the eyelid are angiosarcoma and Kaposi's sarcoma. The eyelid may be involved by orbital vascular lesions, such as lymphangioma, that may extend anteriorly.

Capillary (infantile) hemangioma

This is the most common vascular tumor of the eyelid. It is usually congenital and manifests at birth or within the first couple of weeks. Typically, it grows rapidly during the first 6–12 months, and after a stable period, it involutes gradually until the age of 4–7 years.[

37,

39] It may involve the conjunctiva and the orbit.

Clinically, there are two variants such as superficial and deep. The superficial lesions, which are localized to the epidermis and dermis, are elevated, reddish-purple in color and of a soft consistency, with small surface invaginations – hence the term “strawberry nevus” []. They bleach by application of direct pressure. Involvement of the eyelid margin is common. The deep variant is in the subcutaneous tissue and is bluish in color. The lesion's size is very variable, from small lesions located in one eyelid to a very large lesion involving both eyelids and the periocular region.

Diffuse infantile capillary hemangioma covers the left side of the face

Histopathologically, the lesion is composed of lobules of capillaries separated by sparse fibrous septae []. The capillaries may infiltrate the underlying subcutaneous lesion and muscle. The morphology of the lesion changes with age. While early, immature lesions exhibit plump endothelial cells that may obliterate the vascular lumina, in later stages, the endothelial cells become attenuated, the capillary lumina increase, the fibrous septae are thickened, and the capillary lobules may be replaced by adipose tissue. Mitotic figures can be seen; however, these lesions are benign.[

5,

37]

Histopathologic pictures of capillary hemangioma showing lobules of capillaries separated by fibrous tissue (H and E, ×4)

Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain)

This is a diffuse congenital, mostly unilateral, vascular malformation of the face with involvement of the eyelids and periocular area. It always presents at birth and may become darker and more prominent over time; it never disappears on its own. Clinically, the lesion is flat, exhibits a deeper, more purple hue than capillary hemangioma and unlike capillary hemangioma, it does not bleach on pressure. About 10% of the patients with nevus flammeus of the eyelid are associated with Sturge–Weber syndrome. In such cases, the brain may be involved, and glaucoma is common.[

40,

41]

Histopathologically, nevus flammeus is composed of large dilated cavernous spaces in the dermis.[

5]

Cavernous hemangioma

Cavernous hemangioma is rare in the eyelid. Typically, it arises in the second to fourth decades of life. It demonstrates a slow progressive enlargement and does not regress spontaneously. The lesion is usually not well-circumscribed. The color depends on its depth. The superficially located lesion has a bluish color while the deeper-located lesions may display little or no change of the overlying skin. Cavernous hemangioma of the eyelid may be associated with several syndromes.

Histopathologically, cavernous hemangioma is composed of large, dilated, blood-filled vascular spaces lined by a flat layer of endothelium. The blood spaces may also contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages and scattered lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. Since the lesion may be separated from the systemic blood supply, it may show thrombosis, phlebitis, fibrosis of the septae, and calcifications.[

5]

Kaposi's sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma of the eyelid is rare in immunocompetent, usually elderly men, and is more common in immunodeficient patients, mainly with AIDS. It may appear as a solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or diffuse, blue subcutaneous lesion.[

42]

Histologically, Kaposi's sarcoma is composed of a spongy network of endothelial cells that form slit-like vascular spaces surrounded by spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells and collagen.

Pyogenic granuloma

This is the most common acquired vascular lesion of the eyelid. The term “pyogenic granuloma” is a misnomer since it is neither pyogenic nor granuloma. This reddish-pink mass may occur anywhere in the eyelid, usually following trauma or surgery, grow rapidly, and may bleed easily when touched.

Histopathologically, the lesion is composed of an exuberant mass of granulation tissue with prominent radiating capillaries extending from the narrow base of the pedunculated lesion. The stroma is edematous with mixed inflammatory infiltrates.[

5,

37]

Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors of the eyelid originate from peripheral nerves. The more common benign tumors are plexiform neurofibroma, associated with neurofibromatosis Type I (von Recklinghausen disease), solitary neurofibroma, and schwannoma. The malignant tumors are rare and include the malignant peripheral nerve tumors and Merkel cell tumor. The eyelids may be involved in the more common neurogenic tumors of the orbit.

Plexiform neurofibroma

The eyelid involvement by plexiform neurofibroma in von Recklinghausen disease is a common finding in these patients who may present a typical S-shaped curve in the margin of the upper eyelid. Most of these patients present with ptosis and fullness of the eyelid without change in the skin color over the lesion. The lesions can be solitary, diffuse, or multifocal and can be continuous in the orbit.[

43]

Histopathologically, each neurofibromatous unit is circumscribed by a thickened perineurium, which contains axons, Schwann cells, and endoneural fibroblasts.

Solitary neurofibroma

Solitary/isolated/localized neurofibroma is a circumscribed, although nonencapsulated, lesion that may be seen in the third to fifth decades of life in patients without a medical history of neurofibromatosis. It may resemble chalazion.

Histopathologically, the lesion may have pseudocapsule, but a true perineurium is not discerned. The lesion is composed of many bundles of peripheral nerve sheath cells with comma-shaped nuclei. The stroma shows deposits of hyaluronic acid and various amounts of collagen.[

44]

Schwannoma (neurilemmoma)

This is a benign tumor that rarely appears in the eyelid. Multiple schwannomas can occur in patients with neurofibromatosis while solitary tumors are not associated with this disease. Clinically, it appears as a slow-growing, firm, well-defined mass that can simulate a chalazion.[

45]

Histopathologically, it is an encapsulated lesion that is composed of compact spindle cells (Antoni A pattern) or larger, round clear cells (Antoni B pattern), or a combination of the two patterns.

Merkel cell tumor (cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma)

Merkel cell tumor is a rare primary malignant cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasm of older patients which arises from Merkel cells, which are specialized neuroendocrine receptor cells of the skin and mucous membrane. It can develop in the eyelid and eyebrow region. Clinically, it presents as an asymptomatic, rapidly progressing pink/red/violet-colored nodule, mostly commonly found in the upper eyelid. The tumor may have overlying ulceration or telangiectasia. Local recurrence and metastases are not uncommon.[

46]

Histopathologically, the tumor is composed of lobules of poorly differentiated round cells with round-to-oval nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scanty cytoplasm. Mitotic figures are usually abundant. Positive immunohistochemical staining for neuron-specific enolase, neurofilaments, protein and cytokeratin-20, and negative for S-100 and leukocyte-common antigen are helpful for differentiation from similarly appearing epithelial and neuroendocrine tumors.[

46]

Lymphoid, Plasmacytic, Leukemic, and Metastatic Tumors

These tumors may occur in the eyelid as a primary tumor or primary presentation of systemic disease, or simultaneously with systemic disease, or systemic manifestation will develop at a later stage. They may be contiguous with anterior orbital disease.

Lymphoma of the eyelid is usually B-cell lymphoma; the most common type is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, which is a low-grade lymphoma. Other types of lymphomas in this region are follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, plasmacytoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. Some of the suspected lesions are found to be reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.[

47]

Clinically, it usually presents as a smooth subcutaneous mass without ulceration. T-cell lymphoma is much less common in the eyelid and may be part of mycosis fungoides, which is T-cell lymphoma of the skin. In this case, the skin may be ulcerated.

Leukemic infiltration of the eyelid can occur in patients with systemic acute or chronic leukemia. These cases present as nodular or diffuse subcutaneous eyelid lesions. Leukemia in the eyelid can be the primary presentation of the disease, in the form of granulocytic sarcoma.[

48]

Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, Rosai–Dorfman disease, is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder that involves the lymph nodes, most commonly the cervical lymph nodes, with a protracted clinical course. This disease does not usually threaten life and is often self-limited and can regress spontaneously. Eyelid involvement, sometimes together with orbital involvement, is common.

Histopathologically, these lesions show massive infiltration of large, clear histiocytes, many of which show emperipolesis, namely, phagocytes of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and erythrocytes.[

49]

Metastases to the eyelid present as a rapidly progressive subcutaneous nodule, usually in patients with known cancer. The common primary sites in these cases are breast, lung, and cutaneous melanoma.

Other Eyelid Tumors

The eyelids can be the site of development of other, usually rare, mostly stromal tumors.

Lipomatous tumors include variants of lipomas, benign tumors composed of fat tissue, and rare malignant tumors, primarily liposarcoma, which mostly present as involvement of the eye in an orbital tumor.[

50]

Smooth muscle tumors such as leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, and skeletal muscle tumors such as rhabdomyoma are very rare. The eyelid can be involved in rhabdomyosarcoma of the orbit in children.

The eyelid may be involved in phakomatous tumors such as in neurofibromatosis and vascular phakomatosis as were described earlier. Dermoid cyst, a common hamartoma, often appears clinically as an eyelid tumor, but usually is an orbital lesion with contiguous extension to the eyelid. A localized rare hamartoma in the eyelid is ectopic lacrimal gland, which appears in childhood and may be a part of a complex choristoma, and a source of benign tumors.[

51]

A rare and unique lesion in the eyelid is the phakomatous choristoma, known also as Zimmerman's tumor. This is a congenital tumor of lenticular anlage, lens tissue that probably develops from abnormal migration of cells from the lens placode into the mesodermal eyelid structures. Clinically, it is a smooth, firm subcutaneous mass, usually beneath the inferonasal part of the lower eyelid, which presents in the first few months of life. Histologically, the lesions show similar findings to congenital cataract, including epithelial-like cells surrounded by a thick basement membrane [].[

52]

Histopathological picture of phakomatous choristoma showing cataractous lens tissue surrounded by epithelium, embedded in fibrous tissue (H and E, ×40)

Inflammatory and Infectious Lesions That Simulate Neoplasms

Chalazion

Chalazion is a very common localized lipogranulomatous inflammatory lesion of the sebaceous gland of the eyelid, most often of the meibomian gland. It usually occurs spontaneously due to noninfectious obstruction of sebaceous gland ducts. Clinically, it can present in any part of the four eyelids as a dome-shaped, smooth elevation that may be reddish in color. The lesion may rupture posteriorly through the palpebral conjunctiva and appears as a granulation tissue, or anteriorly through the skin. The chalazion may mimic various real neoplasia, the most important one being SGC.

Histologically, chalazion is a lipogranulomatous reaction to liberated lipid material of the sebaceous gland. Microscopically, it shows formation of granulomas, each centered by a clear space representing lipid globules, that are composed of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells intermixed with acute and chronic inflammatory cells. A pseudocapsule of connective tissue often forms around the lesion [].[

5]

Histopathological pictures of a chalazion showing formation of granulomas around clear spaces representing lipid globules (H and E, ×25)

Molluscum contagiosum

These are common skin lesions, seen more in children, caused by the pox virus that often affects the eyelid and the periocular skin. Clinically, it presents in most cases as multiple small (1–5 mm in diameter) dome-shaped, skin-colored nodules with typical central umbilication in most of them. Lesions in the lid margin may cause follicular conjunctivitis. Molluscum contagiosum is found frequently in patients with AIDS.[

53]

Histopathologically, the epidermis shows invasive acanthosis that forms pear-shaped lobules. The epithelial cells at the surface degenerate and fill the central cavity of the lesion. The centrally located cells are filled by intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, the molluscum bodies, which appear as round-to-oval eosinophilic structures, a single structure in each cell, which become darker toward the surface epithelium [].[

5]

Histopathological picture of molluscum contagiosum showing typical globules of cells filled with intracytoplasmic eosinophilic “molluscum bodies” (H and E, ×40)

Verruca vulgaris

These are common skin lesions that are caused by the wart virus, a DNA virus that belongs to the papova group. Clinically they present as circumscribed, elevated papillomatous hyperkeratotic lesion, resembling squamous papilloma.

Histopathologically, the lesions show papillomatous structures of acanthotic epithelium with hyperkeratosis and often parakeratosis. The infected cells are groups of vacuolated cells with round, deeply basophilic inclusions surrounded by a clear halo.[

5]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bedrossian EH. Embryology and anatomy of the eyelid. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duane's Foundation of Clinical Ophthalmology, Ocular Anatomy, Embryology and Teratology. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 1–24. Ch. 5.

2. Campbell RJ, Sobin LH. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 1998. Tumours of the eyelid; pp. 3–9.

3. Pe'er J. Eyelid tumors: Classification and differential diagnosis. In: Pe'er J, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 9–10. Ch. 2.

4.

Kersten RC, Ewing-Chow D, Kulwin DR, Gallon M. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of cutaneous eyelid lesions. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:479–84. [PubMed]

5. Font RL. Ophthalmic Pathology. An Atlas and Textbook. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996. Eyelids and lacrimal drainage system; pp. 2229–32.

6.

Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Eyelid tumors with reference to lesions confused with squamous cell carcinoma. II. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;69:698–707. [PubMed]

7. Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman's Surgical Pathology. 10th ed. New York: Mosby Elsevier; 2011. pp. 129–213.

8.

Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, James CL, Hsuan JD, Davis G, Selva D. Periocular keratoacanthoma: Can we always rely on the clinical diagnosis? Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1201–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

9.

Person JR. An actinic keratosis is neither malignant nor premalignant: It is an initiated tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:637–8. [PubMed]

10.

Brooks BP, Thompson AH, Bishop RJ, Clayton JA, Chan CC, Tsilou ET, et al. Ocular manifestations of xeroderma pigmentosum: Long-term follow-up highlights the role of DNA repair in protection from sun damage. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1324–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

11.

Wu A, Sun MT, Huilgol SC, Madge S, Selva D. Histological subtypes of periocular basal cell carcinoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2014;42:603–7. [PubMed]

12.

Nasser QJ, Roth KG, Warneke CL, Yin VT, El Sawy T, Esmaeli B. Impact of AJCC 'T' designation on risk of regional lymph node metastasis in patients with squamous carcinoma of the eyelid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:498–501. [PubMed]

13.

Sun MT, Andrew NH, O'Donnell B, McNab A, Huilgol SC, Selva D. Periocular squamous cell carcinoma: TNM staging and recurrence. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1512–6. [PubMed]

14.

Tannous ZS, Mihm MC, Jr, Sober AJ, Duncan LM. Congenital melanocytic nevi: Clinical and histopathologic features, risk of melanoma, and clinical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:197–203. [PubMed]

15.

McDonnell PJ, Mayou BJ. Congenital divided naevus of the eyelids. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:198–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

16.

Shields CL, Kaliki S, Livesey M, Walker B, Garoon R, Bucci M, et al. Association of ocular and oculodermal melanocytosis with the rate of uveal melanoma metastasis: Analysis of 7872 consecutive eyes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:993–1003. [PubMed]

17.

Patel BC, Egan CA, Lucius RW, Gerwels JW, Mamalis N, Anderson RL. Cutaneous malignant melanoma and oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota): Report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 Pt 2):862–5. [PubMed]

18.

Gündüz K, Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC., Jr Periorbital cellular blue nevus leading to orbitopalpebral and intracranial melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2046–50. [PubMed]

19.

Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O'Brien JM, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009;457:599–602. [PMC free article][PubMed]

20. Schoenfield L, Singh AD. Benign squamous and melanocytic tumors. In: Pe'er J, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 17–31. Ch. 3.

21. Pe'er J, Folberg R. Eyelid tumors: Cutaneous melanoma. In: Pe'er J, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 63–8. Ch. 7.

22.

Cook BE, Jr, Bartley GB. Treatment options and future prospects for the management of eyelid malignancies: An evidence-based update. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2088–98. [PubMed]

23. Herwig MC, Loeffler KU. Adnexal tumors. In: Pe'er J, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 63–8. Ch. 37.

24.

Jakobiec FA, Zakka FR. A reappraisal of eyelid eccrine and apocrine hidrocystomas: Microanatomic and immunohistochemical studies of 40 lesions. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:358–74.e2. [PubMed]

25.

Kang SJ, Wojno TH, Grossniklaus HE. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst of the eyelid. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:1065–7. [PubMed]

26.

Esmaeli B, Ramsay JA, Chorneyko KA, Wright CL, Harvey JT. Sclerosing sweat-duct carcinoma (malignant syringoma) of the upper eyelid: A patient report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:441–5. [PubMed]

27.

Hoguet A, Warrow D, Milite J, McCormick SA, Maher E, Della Rocca R, et al. Mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the eyelid: Diagnostic and prognostic considerations. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:585–92.e2. [PubMed]

28.

Figueira EC, Danks J, Watanabe A, Khong JJ, Ong L, Selva D. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the eyelid: Case series and review. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:417–23. [PubMed]

29.

Carreras B, Jr, Lopez-Marin I, Jr, Mellado VG, Gutierrez MT. Trichofolliculoma of the eyelid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;62:214–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

30.

Hidayat AA, Font RL. Trichilemmoma of eyelid and eyebrow. A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:844–7. [PubMed]

31.

Levy J, Ilsar M, Deckel Y, Maly A, Anteby I, Pe'er J. Eyelid pilomatrixoma: A description of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:526–35. [PubMed]

32.

Singh AD, Mudhar HS, Bhola R, Rundle PA, Rennie IG. Sebaceous adenoma of the eyelid in Muir-Torre syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:562–5. [PubMed]

33.

Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Jr, Shields CL. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular region: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:103–22. [PubMed]

34.

Sinard JH. Immunohistochemical distinction of ocular sebaceous carcinoma from basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:776–83. [PubMed]

35.

Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid, eyebrow, caruncle, and orbit. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1968;72:619–42. [PubMed]

36.

Muqit MM, Roberts F, Lee WR, Kemp E. Improved survival rates in sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:49–53. [PubMed]

37. Vemuganti GK, Honavar SG. Stromal tumors. In: Pe'er J, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumors. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 79–94. Ch. 9.

38.

Codère F, Lee RD, Anderson RL. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma of the eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:60–3. [PubMed]

39.

Jackson R. The natural history of strawberry naevi. J Cutan Med Surg. 1998;2:187–9. [PubMed]

40.

Tallman B, Tan OT, Morelli JG, Piepenbrink J, Stafford TJ, Trainor S, et al. Location of port-wine stains and the likelihood of ophthalmic and/or central nervous system complications. Pediatrics. 1991;87:323–7. [PubMed]

41.

Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, Viaño J. Sturge-Weber syndrome: Study of 55 patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:301–7. [PubMed]

42.

Brun SC, Jakobiec FA. Kaposi's sarcoma of the ocular adnexa. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:25–38.[PubMed]

43.

Chaudhry IA, Morales J, Shamsi FA, Al-Rashed W, Elzaridi E, Arat YO, et al. Orbitofacial neurofibromatosis: Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:583–92.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

44.

Stagner AM, Jakobiec FA. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the eyelid dermis: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;32:40–5. [PubMed]

45.

Butt Z, Ironside JW. Superficial epithelioid schwannoma presenting as a subcutaneous upper eyelid mass. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:586–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

46.

Merritt H, Sniegowski MC, Esmaeli B. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular region. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1128–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

47.

Coupland SE, Krause L, Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Foss HD, Hummel M, et al. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the ocular adnexa. Analysis of 112 cases. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1430–41. [PubMed]

48.

Zimmerman LE, Font RL. Ophthalmologic manifestations of granulocytic sarcoma (myeloid sarcoma or chloroma).The third Pan American Association of Ophthalmology and American Journal of Ophthalmology Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:975–90. [PubMed]

49.

Levinger S, Pe'er J, Aker M, Okon E. Rosai-Dorfman disease involving four eyelids. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:382–4. [PubMed]

50.

Thyparampil P, Diwan AH, Diaz-Marchan P, Grekin SJ, Marx DP. Eyelid lipomas: A case report and review of the literature. Orbit. 2012;31:319–20. [PubMed]

51.

Obi EE, Drummond SR, Kemp EG, Roberts F. Pleomorphic adenomas of the lower eyelid: A case series. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:e14–7. [PubMed]

52.

Zimmerman LE. Phakomatous choristoma of the eyelid. A tumor of lenticular anlage. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71(1 Pt 2):169–77. [PubMed]

53.

Averbuch D, Jaouni T, Pe'er J, Engelhard D. Confluent molluscum contagiosum covering the eyelids of an HIV-positive child. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:525–7. [PubMed]

James Kasenchak, MD, and Gregory Notz, DO, Danville, Pa.

PUBLISHED 5 APRIL 2016

Eyelid Lesions: Diagnosis and Treatment

A look at some of the common eyelid lesions that you may encounter in practice, their risk factors and treatment options.

Eyelid lesions are more often than not benign. Accurate diagnosis by an ophthalmologist is based on history and clinical examination. When in doubt, any suspicious lesion should undergo biopsy. Here we offer a brief review of some of the more common eyelid lesions that an ophthalmologist may encounter in a general practice. Background, ExamTo diagnose eyelid lesions one must first understand the anatomy of the eyelid and especially the eyelid margin and its characteristics. The eyelid margin consists of the skin, muscle, fat, tarsus, conjunctiva and adnexal structures including the approximately 100 eyelashes, glands of Zeis, glands of Moll, meibomian glands and the associated vascular and lymphatic supply. The examination of an eyelid lesion begins with history. History should include chronicity, symptoms (tenderness, change in vision, discharge), and evolution of the lesion. Other pertinent points include a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, fair skin or radiation therapy. Physical examination should include assessment of location

, the appearance of the surface of the lesion and surrounding skin including adnexal structures. The clinician should be assessing

for any ulceration with crusting or bleeding, irregular pigment, loss of normal eyelid architecture, pearly edges with central ulceration, fine telangiectasia or loss of cutaneous wrinkles. Finally, a physical examination of the patient should include palpation of the edges and/or fixation to deeper tissues, and assessment of regional lymph nodes and the function of cranial nerves II-VII. A picture can be priceless for following disease progression or response to treatment. Although experienced clinicians may feel comfortable in their diagnosis, any doubt in clinical judgment should push the clinician for a histologic examination. Reports of clinically accurate diagnoses ranged from 83.7 percent to 96.9 percent with between 2 percent and 4.6 percent thought to be clinically benign but found to be histologically malignant.1,2ClassificationAmong tumors encountered by ophthalmologist

the most common neoplasms are those of the eyelid. Benign lesions of the eyelid represent upwards of 80 percent of eyelid neoplasms, while malignant tumors account for the remaining, with basal cell cancer the most frequent malignant tumor.3 It can be helpful to categorize eyelid lesions into inflammatory, infectious and neoplastic.

|

| Figure 1. Multiple chalazia located in the right lower lid of a 74-year-old female. They were treated with incision and drainage, and the biopsy was consistent with chalazion. |

Inflammatory Lesions• Chalazion presents as chronic, localized swelling of the eyelid and typically affects the meibomian glands or glands of Zeis (See Figure 1). Data on the frequencies is difficult to come by, but in one recent review chalazia represented nearly half of all eyelid lesions encountered in an ophthalmology practice.3 Conservative treatment with warm compresses or topical steroids is often sufficient. Surgical management includes transconjunctival incision and curettage. If excision is performed it is recommended that histopathologic confirmation of the excised lesion be performed every time.1 Alternatively, management with intralesional triamcinolone can be used although this approach carries with it complications of pigment changes or more devastating central retinal artery embolization. Intralesional dexamethasone is a safer alternative.Infectious Lesions• Molluscum contagiosum presents as pale, waxy and nodular cysts, classically with central umbilication. The patient is typically young, although there is increased incidence with more exuberant cases seen in AIDS patients due to reduced T cell count. They form secondary to infection from a DNA poxvirus and can present as a follicular

conjunctivitis or lid nodules. The lid lesions may be misdiagnosed as a number of other eyelid lesions including basal cell carcinoma, papilloma, chalazion and sebaceous cyst. There is no predilection for the upper or lower eyelid and the local immune response will often be sufficient to eliminate the virus. Other treatment options include excision, cryotherapy or curettage.4Neoplastic Lesions, Benign• Squamous cell papillomas are formed from proliferation

of epidermis and present either pedunculated, broad-based or white and hyperkeratotic lesions

forming fingerlike projections.5 Treatment is usually not required except for cosmetic removal.

| Table 1. Malignant Eyelid Lesions Demographics and Risk Factors |

| Malignant Lesions | Age | Sex Predilection | Location | Race | Risk Factors |

| Basal Cell3,12 | 70 | Equal | Lower, medial canthus | Caucasians of Celtic ancestry | Fair skin, sun exposure, smoking |

| Squamous Cell3,12 | 65 | Male | Lower | Caucasians and Asians | Fair skin, sun exposure, exposure to radiation |

| Sebaceous Gland3,14 | 65-70 | Female | Upper | Asian | Cancer syndromes and

immunosuppression |

| Merkel Cell3,10 | 75 | Female | Upper | Caucasians | Immunosuppression |

| Metastasis17 | >50 | Equal | Upper slightly | None | Systemic cancer |

| Lymphoma17 | 65 | Female | No predilection | Caucasians | Systemic lymphoma |

| Melanoma18 | 60-80 | None | Lower | Caucasians | Sun exposure |

• Epidermal inclusion cysts present as elevated, smooth and progressively growing cysts that arise from entrapment of epidermal tissue in the dermis. Rupture with release

of keratin can cause an inflammatory foreign-body reaction.6Treatment involves excision with retention of the surrounding capsule, simply decapitating the head of the cyst allowing granulation tissue to form.• Acquired melanocytic nevi are frequently molded to the eyelid margin and represent clumps of melanocytes at the epidermis and dermis. Not clinically apparent at birth, they increase in pigmentation at puberty. In the second decade

they tend to present as elevated, pigmented papules. Later, the superficial pigmentation is lost, and an elevated, but amelanotic lesion remains.6 They usually require no treatment, but malignant

transformation of a junctional or compound nevus can rarely occur and requires excision.• Seborrheic keratosis is an acquired benign condition affecting elderly patients. Classically the lesions have a greasy and stuck-on appearance with varying degrees of pigmentation. Excision is sometimes required but recurrence is quite high. • Hidrocystoma, also known as sweat ductal cysts, are caused by blockage of a sweat duct. They present as small (average of 4 mm) soft, smooth and transparent lesions.5,7 Eccrine hidrocystoma often present as multiple cysts along the eyelids but do not involve the eyelid margin. Apocrine hidrocystomas characteristically transilluminate, involve the eyelid margin, and are associated with a hair follicle. The apocrine variety also tend

to have a bluish color with yellow deposits. Cystic basal cell carcinoma is in

the differential and specimens should be sent to pathology. • Xanthelasmas present as yellowish plaques, usually in the medial canthal areas of either the upper or lower eyelids. The plaques are filled with lipid-laden macrophages. Patients usually have normal serum cholesterol levels but it is prudent to check lipid levels, as they can be associated with hypercholesterolemia.6 Treatment options include superficial excision, CO2 laser ablation or topical 100% trichloroacetic acid.

|

| Figure 2. Basal cell carcinoma of the left lower lid in a 57-year-old male. Note the pearly edges and central scab. Initial biopsy was consistent with BCC. The condition is treated with Mohs’ surgery with reconstruction with a Hughes flap by an oculoplastic specialist. |

Neoplastic Lesions, Premalignant• Actinic keratosis presents as round, scaly, hyper-keratotic plaques that have the texture of sandpaper. They are the most common precancerous skin lesion and usually affect elderly persons with fair complexion and excessive sun exposure. Malignant transformation for a single plaque is less than 1 percent per year.6 Observation is an option, but excisional biopsy is usually recommended to establish a diagnosis. Multiple lesions can be treated with cryotherapy, imiquimod 5% cream or other newer topical agents. • Keratoacanthoma presents as flesh-colored papules usually on the lower eyelid in patients with chronic sun exposure or immunocompromised patients. This is now considered a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma in which dome-shaped hyperkeratotic lesions develop and can grow rapidly, with involution and regression at up to one year, once a keratin-filled crater develops.8 After diagnosis with incisional biopsy has been made, current recommendations include complete surgical excision.6Neoplastic Lesions—Malignant• Basal cell carcinoma represents 80 to 92.2 percent of malignant neoplasms in the periocular region.9 The localized nodular subtype is the “classic” lesion and presents most frequently on the lower lid at the medial canthus as a firm, raised, pearly nodules with fine telangiectasias (See Figure 2).11 A less common form of BCC, but more locally aggressive is the morpheaform

type; these lesions lack ulceration,

and appear as an indurated white to yellow plaque with indistinct margins.8Patients are typically middle-aged or older and often fair-skinned, although it can occur in children and persons of African ancestry.12 BCC in younger patients has a more aggressive growth pattern and does not demonstrate the latency period seen in older patients.12 Treatment is primarily with Mohs’ micrographic surgery followed by eyelid/facial repair with oculoplastics. Orbital invasion occurs in less than 5 percent of BCC and most commonly the lesions are at the medial canthus.8,12 Signs of orbital invasion include a fixed orbital mass, restrictive strabismus and globe displacement or destruction.9 CT or MRI is indicated to determine the extent of the disease. Once penetration reaches deep to the septum, local excision is very difficult. Nests of basal cells often hide, and this leads to more aggressive surgery (including orbital exenteration). Some cancer centers prefer external beam radiation followed by surgical removal in these advanced cases. • Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common eyelid malignancy, occurring in the lower lid approximately 60 percent of the time.13 SCC lacks the pathognomonic features, which allows for differentiation from precursor lesions including actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease (squamous cell cancer in situ) and radiation dermatitis.8,12 The presentation is often with a painless nodular lesion with irregular rolled edges, pearly borders, telangiectasias and central ulceration, similar to BCC.12 The clinical diagnosis has been reported to be accurate anywhere from 51 percent to 62.7 percent of the time.13 Patients are generally males older than 60 and often have a history of other skin lesions requiring excision.11Predisposing factors include both extrinsic factors, such as ultraviolet light, exposure to arsenic/hydrocarbons/radiation, HPV infection or immunosuppressive drugs and burns; and intrinsic factors of albinism and xeroderma pigmentosa

.11,13 Metastasis of the lesions is most commonly through the lymphatic system, and early detection of lymph node involvement is essential to improve the prognosis.9,11SCC invades along the trigeminal, oculomotor and facial nerves and can present as asymptomatic perineural invasion detected on histologic examination or symptomatic perineural invasion. SCC with perineural invasion has a recurrence rate of up to 50 percent, and postoperative radiotherapy for all SCC with perineural invasion has been suggested.9• Sebaceous carcinoma originates in the meibomian glands or the glands of Zeis and presents clinically as yellowish discoloration due to its lipid content; it can mimic blepharoconjunctivitis, chronic chalazia, BCC, SCC or other tumors (See Figure 3).8 The lesions most commonly affect women aged 65 to 70 in along the upper lid.14 It can present as loss of eyelashes, destruction of Meibomian orifices or chronic unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis. SC affects all races, but Asians in particular, and represents the most common or second most common periocular malignancy in this group.3,9The diagnosis can be missed on initial biopsy,

and may require multiple biopsies or special stains. Superficial

biopsy is often not sufficient and can miss the underlying tumor; therefore a pentagonal full-thickness excision or punch biopsy may be necessary to make the diagnosis. Biopsy specimens with intraepithelial involvement of the conjunctiva should raise the suspicion for orbital invasion.8

|

| Figure 3. Sebaceous carcinoma of the left lower lid in a 52-year-old female. Patient presented with chronic unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis for 12 months, madarosis and eyelid lesion. Incisional biopsy showed sebaceous gland carcinoma. Definitive treatment should be undertaken by an experienced oculoplastic specialist or multidisciplinary team. |

Although the etiology is not usually known, there is an association with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome thought to be a subtype of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. If SC is identified the patient should be evaluated for this syndrome.11 Mortality rates within industrialized countries have fallen to 9 to 15 percent; poor prognostic factors include duration longer than six months; vascular and lymphatic involvement; orbital extension; multicentric origin; intraepithelial carcinoma or pagetoid spread into the conjunctiva, cornea, or skin; upper lid location; and previous radiation.14• Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid presents in elderly Caucasian women, average

age of 75, with immunosuppression being a risk factor. Half of all MCCs are located in the head and neck, and between 5 and 10 percent occur in the eyelids.10 MCC presents in the upper lid as a painless, red-purple vascularized nodule, sparing of the overlying epidermis. In 20 to 60 percent of patients, there is lymph-node positivity at presentation and distant metastases appear within two years 70 percent of the time.15 This can be an aggressive, fatal cancer that requires judicious biopsy and systemic management by oncology. Tumor size and metastasis at presentation are the most important prognostic factor with MCC tumors. The evaluation for tumor-lymph node-metastasis starts after the histologic diagnosis. Regarding treatment, the tumor responds well to radiation therapy, but primary treatment of the tumor is with excision and wide margins or Mohs’ surgery.10• Metastasis to the eyelid is rare and represents less than 1 percent of malignant eyelid tumors; it usually occurs in the course of widespread