How Diabetes Leads to Blindness: Understanding Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Treatment Options

Yesterday, I saw a patient who had end-stage diabetic retinopathy and was losing her vision. She did not know years ago that diabetes was curable—knowledge that might have saved her sight.

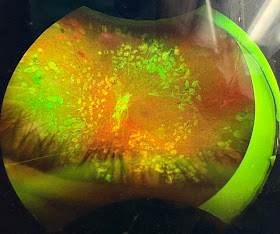

Below is a photo of her retina, shared with her permission, showing the devastating effects of this condition.

Diabetes continues to be a preventable cause of blindness, yet it claims vision unnecessarily.

Decreasing your carbohydrate intake is the most important step you can take to prevent diabetes. Today, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are inexpensive and accessible for most patients. Talk to your doctor about getting a CGM so you can track your glucose levels and determine which medications or lifestyle changes are right for you. Here’s more information below on how diabetes causes blindness and the treatments available to stop it.

How Diabetes Damages the Eyes

The retina relies on a delicate network of blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients. In diabetes, persistently high blood sugar weakens these vessels, causing them to leak fluid, bleed, or become blocked. This condition, known as diabetic retinopathy, progresses through stages:

- Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR): The early stage, where blood vessels weaken, form microaneurysms (small bulges), and may leak fluid or lipids into the retina, causing swelling (edema) or hemorrhages. Vision may still be normal or mildly affected.

- Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PDR): The advanced stage, where the retina, starved of oxygen due to blocked or damaged vessels, triggers the growth of new, abnormal blood vessels (neovascularization). This is the body’s attempt to compensate, but it backfires.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Closer Look

In PDR, the new blood vessels are fragile and prone to bleeding. They grow not only on the retina but sometimes into the vitreous, the gel-like substance filling the eye. These vessels often appear sclerotic—hardened, scarred, or thickened—due to repeated damage and repair attempts. This sclerosis can make them less functional and more likely to rupture, leading to:

- Vitreous hemorrhage: Bleeding into the vitreous, which clouds vision.

- Tractional retinal detachment: Scar tissue from sclerotic vessels pulls the retina away from its normal position, severely impairing sight.

- Neovascular glaucoma: Abnormal vessels grow into the eye’s drainage system, increasing pressure and damaging the optic nerve.

Without intervention, PDR can result in irreversible blindness. The sclerotic appearance of these vessels is a hallmark of chronic damage, reflecting the progression from leaky capillaries to a chaotic, fibrotic network.

Treatment Options for PDR

Fortunately, treatments can halt or slow PDR’s progression. Two primary approaches are panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) and anti-VEGF intraocular injections. Let’s break them down.

Panretinal Photocoagulation (PRP)

PRP is a laser therapy designed to preserve central vision by sacrificing peripheral vision. Here’s how it works:

- A laser creates controlled burns across the peripheral retina, targeting areas with poor blood flow (ischemia).

- These burns reduce the retina’s oxygen demand, discouraging the growth of abnormal blood vessels.

- By stabilizing the retina, PRP prevents further hemorrhages or detachments.

Pros:

- Long-term effectiveness in halting neovascularization.

- Reduces the risk of severe vision loss in advanced PDR.

- Often a one-time or limited-session procedure.

Cons:

- Loss of peripheral vision and night vision due to laser damage.

- Temporary discomfort or blurred vision post-treatment.

- May not address existing swelling (macular edema) or bleeding.

PRP is typically recommended for patients with widespread ischemia or those at high risk of blindness, but it’s less effective for early-stage disease or macular edema alone.

Anti-VEGF Intraocular Injections

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a protein that drives abnormal blood vessel growth in PDR. Anti-VEGF drugs block this protein, shrinking new vessels and reducing leakage. These medications are injected directly into the eye, usually every 4-6 weeks initially, with frequency tapering based on response. Here’s a list of commonly used anti-VEGF drugs:

- Bevacizumab (Avastin)

- What it is: Originally developed for cancer, it’s used off-label for eye conditions.

- Pros: Cost-effective (often the cheapest option), widely available.

- Cons: Not FDA-approved for ocular use, so dosing relies on physician discretion; shorter duration of effect.

- Best for: Patients seeking affordability or those unresponsive to other options.

- Ranibizumab (Lucentis)

- What it is: Specifically designed for eye conditions, FDA-approved for diabetic retinopathy.

- Pros: Highly effective, lower risk of systemic side effects due to its targeted design.

- Cons: Expensive; requires frequent injections initially.

- Best for: Patients prioritizing efficacy and safety with insurance coverage.

- Aflibercept (Eylea)

- What it is: Another FDA-approved option with a longer duration of action.

- Pros: May require fewer injections (every 8-12 weeks after loading doses), potent VEGF suppression.

- Cons: High cost; potential for injection-related complications.

- Best for: Patients seeking convenience and fewer visits.

- Brolucizumab (Beovu)

- What it is: A newer, long-acting anti-VEGF drug.

- Pros: Extended dosing intervals (up to 12 weeks), strong efficacy.

- Cons: Higher risk of inflammation (e.g., retinal vasculitis), less long-term data.

- Best for: Patients willing to try newer options under close monitoring.

- Faricimab (Vabysmo)

- What it is: A dual-action drug targeting VEGF and angiopoietin-2, approved in 2022.

- Pros: Longer intervals (up to 16 weeks), potentially better control of vessel stability.

- Cons: Newer, so cost and long-term outcomes are less established.

- Best for: Patients with resistant PDR or coexisting macular edema.

How They Work: These drugs shrink sclerotic, leaky vessels and prevent new ones from forming, improving retinal health. They’re often combined with PRP or used alone in earlier stages.

Why Choose One Anti-VEGF Over Another?

Patients and doctors weigh several factors when selecting an anti-VEGF medication:

- Cost: Bevacizumab is the most affordable, while ranibizumab and aflibercept are pricier but often covered by insurance. Brolucizumab and faricimab may fall in between but vary by region.

- Frequency: Aflibercept and faricimab offer longer intervals, appealing to patients with busy schedules or difficulty accessing care.

- Safety Profile: Ranibizumab and aflibercept have extensive safety data, while brolucizumab’s inflammation risk may deter some.

- Response: Some patients respond better to one drug due to individual biology—trial and error may be needed.

- Insurance and Availability: Coverage often dictates choice, especially for branded drugs like Lucentis or Eylea.

PRP vs. Anti-VEGF: A Combined Approach?

For severe PDR with sclerotic vessels and active bleeding, PRP remains the gold standard to stabilize the retina long-term. However, anti-VEGF injections are increasingly used first to reduce vessel growth and swelling, delaying or reducing the need for PRP. In some cases, both are combined: anti-VEGF to shrink vessels quickly, followed by PRP for lasting control.

Preventing Blindness: The Bigger Picture

Diabetes-related blindness isn’t inevitable. Regular eye exams, tight blood sugar control, and early intervention can stop PDR in its tracks. If you or a loved one has diabetes, consult an ophthalmologist annually—or sooner if vision changes occur.

In summary, proliferative diabetic retinopathy transforms fragile, sclerotic blood vessels into a vision-threatening crisis. Treatments like PRP and anti-VEGF injections offer hope, with options tailored to cost, convenience, and clinical needs. By understanding these choices, patients can work with their doctors to protect their sight and maintain quality of life.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.